How non-party socialists built the core of the State Museum of the Revolution, only to be pushed aside

“Cadres decide everything!”—the sharp catch-phrase that Stalin delivered on 4 May 1935 at the graduation of the military academies—was instantly elevated to a state slogan, and soon became the rationale for the Great Terror. If the “right” people were to decide everything, then the “wrong” ones had to be removed. History, however, is paradoxical: it was precisely those “wrong” people—figures outside the Bolshevik Party—who laid the foundations of the country’s chief monument to revolutionary memory, the State Museum of the Revolution.

From Prison Aid to Museum Display

After the February Revolution of 1917 hundreds of émigrés and exiles streamed back to Petrograd. Among them were the legendary Narodnaya Volya veteran Vera Figner, freed after twenty-two years in solitary confinement, and her comrade Alexandra T. Shakol, a former anarchist who had taken part in a daring 1906 prison raid. Figner revived the Political Red Cross, which assisted political prisoners throughout the collapsing Russian Empire; Shakol worked at her side.

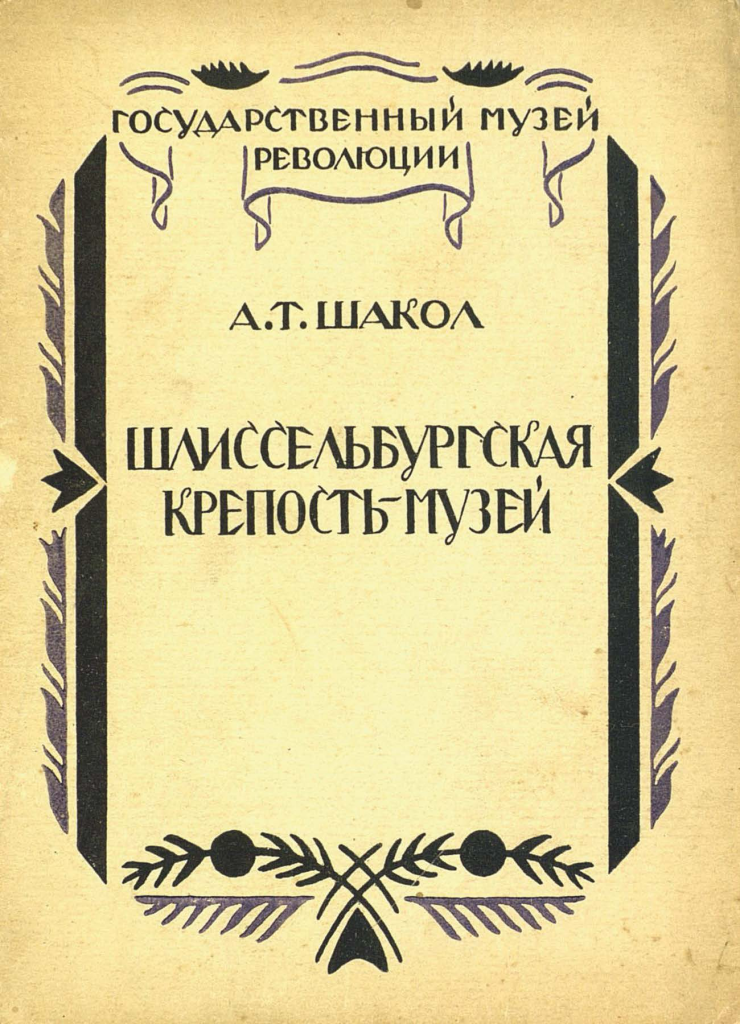

In 1919 Shakol became secretary of the founding assembly of the State Museum of the Revolution (SMR) and soon headed its Department of Tsarist Hard-Labour Prisons and Exile, a post she held until her dismissal in 1935. Her department curated the history of the imperial penal system, turned the Shlisselburg and Peter-and-Paul fortresses into museum sites, tracked down surviving “old lags,” interviewed them, and hunted for documents in provincial archives. She poured her soul into the work, telling Figner in one letter that her exhibitions were “like children” to her, each designed to keep alive the memory of those who had suffered for the revolution.

“Non-Party Socialism”: Who Were They?

Almost none of these museum workers were Bolsheviks.

- The 1920s director, Mikhail Kaplan, had been a Menshevik.

- Shakol remained an anarchist at heart.

- Many restorers and guides were formally unaffiliated.

Shakol herself coined the phrase “non-party activism”—a left-wing, socialist stance that refused to submit to party hierarchy. In 1928, as repression mounted, she wrote bitterly to Figner: “It is hard to live the life of a non-party activist; we are the superfluous ones at our own revolutionary feast.”

The Delicate Craft of Memory

Why did these outsiders form the museum’s core?

- Experience – All of them had lived underground and knew the sources and idioms of clandestine culture.

- Motivation – Their drive sprang not from orders above but from an inner duty “to save the blood and tears” of their comrades.

- Networks – Through the Red Cross and émigré circles they could easily trace ex-prisoners, manuscripts, and artefacts.

Marx wrote that dead labour accumulates in capital; by the same dialectic, their “accumulated defeats” became the cultural capital of the revolution.

How Stalinism Devoured the Museum

By the early 1930s the slogan “cadres decide everything” had become a directive of total loyalty. Appointees—young Communists, often with scant curatorial skill but impeccable ideological credentials—were planted throughout the museum. The old guard was not sacked overnight (without them the showcases would have gone dark), but diluted: bosses were reshuffled, “reliable” supervisors inserted, labels rewritten.

The final purge came in 1935, when Shakol was removed; she slips from the archives as quietly as she once lugged heavy prison ledgers for her “child-exhibits.” The newcomers spoke the right slogans, yet, as veterans lamented, “the living flame of the revolution” no longer burned in them.

Why This Story Matters Today

Because it reminds us of a simple truth: museums are, above all, made of people. The generation of “non-party socialists” proved that preserving memory is itself a political act. Once they were pushed out, the living ethic of solidarity gave way to the granite “canons” of late Stalinism.

My chapter on Shakol and her colleagues will soon appear in the collection 50 Shades of Red. There I explore in greater depth how individual revolutionary trajectories were woven into the museum’s fabric, and what “non-party socialism” can mean to historians now.

History is made by people—even when the authorities insist that cadres are only cogs in a machine.

Watch for the book, and share your own stories of those whose names slipped from official lists yet without whom the revolution itself cannot be understood.